Do we give as good as we get? That’s the subject of Adam Grant’s TED talk, “Are you a giver or a taker?”. While many of us strive to be Givers (“What can I do for you?”), our workplaces nevertheless tend to contain their fair share of self-serving Takers: “What can you do for me?”

Grant surveyed 30,000 people worldwide and found that most people fall firmly in the middle of these definitions; they’re so-called Matchers, who take a “quid-quo-pro” approach by trying to give back to as many people as help them. Of the two headline types, significantly more people claim to identify as Givers than Takers - which is perhaps unsurprising, as who’s going to admit to being a net negative for their organisation?

You might think that it’s culturally and ethically sensible to position yourself as a Giver, but that’s when the data starts to get interesting.

Givers succeed, but they also struggle

When looking at the performance of different personality types within organisations, Grant found that Givers were, perhaps unsurprisingly, the worst performers: they’re so keen to help others that it’s often at the expense of completing their own work. However, their good nature has a ripple effect which benefits the organisation; when people’s lives are enriched by a Giver, it makes them want to reciprocate more often themselves.

However, the data shows that Givers are represented at both extremes of the performance spectrum: both the worst and the best results can be found from Givers.

- Protect Givers from burnout: You can be a Giver without making grand gestures. The correct “five-minute favour” which connects the right people at the right time can lead to almost effortless success.

- Encourage help-seeking: People with a Giver mentality are often reticent to ask for help themselves; if we normalise this behaviour, we can ensure that our Givers get as good as they give.

- Get the right people on the bus: If you want to build a culture of reciprocity, you don’t necessarily need to fill your team with Givers, but it’s critical to weed out the Takers, as they can suck the life out of a team much more quickly than a Giver can refill it.

So, if Takers sit squarely in the middle performance-wise, how do we handle them?

Takers may succeed, but only in the short term

Although a Taker may be able to achieve quick wins by harnessing their influence to get work done for them, any gains tend to cancel themselves out. With the majority of people being Matchers, who believe in a fair trade of services, they therefore wise-up to the Takers in their organisation very swiftly.

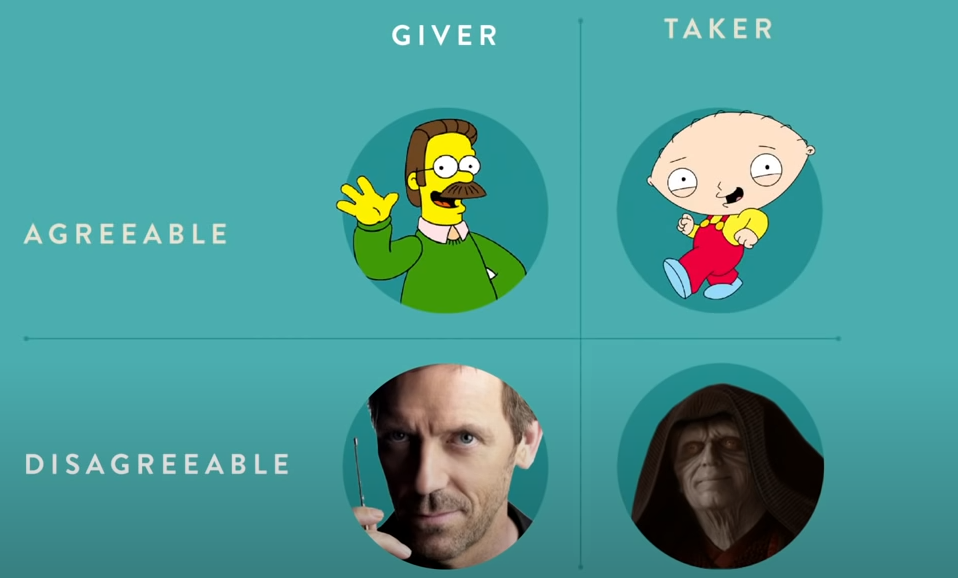

However, our ability to identify Givers and Takers is often skewed by whether people behave in an agreeable or disagreeable manner. At the extremes, the “agreeable givers” and “disagreeable takers” are easy to spot, but we are sometimes confused by “disagreeable givers” (surly yet helpful people) and “agreeable takers” (people who are good at manipulating others to their needs).

Grant summarises that “the most meaningful way to succeed is to help other people to succeed”, and to introduce a culture of “Pronoia” (the opposite of paranoia: the belief that other people are actively plotting to help you).

Key takeaways 📝

- Givers are beneficial to an organisation, but are at risk of exploitation.

- At the very least, aspire to be a Matcher - somebody who gives as good as they get.

- Be on the lookout for self-serving “agreeable takers”.