There’s an age-old adage (one of those that’s so widely-spread that nobody can agree on who said it first): “Choose a job that you love, and you’ll never have to work a day in your life”. And while sometimes we all just need to pay the bills, or a straightforward role that fits around a busy home life, that’s why many of us seek to make a career in an area where we have a personal passion.

It’s a thought that was echoed by Steve Jobs, a man of many wise soundbites, who stated in a 2005 Stanford University commencement speech:

“Your work is going to fill a large part of your life, and the only way to be truly satisfied is to do what you believe is great work. And the only way to do great work is to love what you do.”

Yet when we follow our passions, or tell ourselves that we’re doing something “for the love of it”, we’re leaving ourselves open to heightened expectations, and even exploitation. So what’s the secret to making a living in an area that you’re passionate about?

Diagramming the conundrum

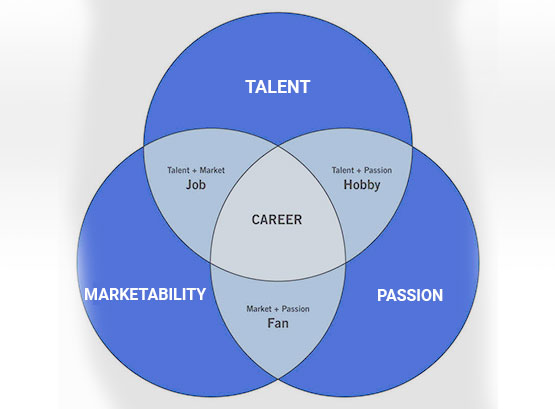

Earlier this year, a talk at the TestBash Careers event by Kiruthika Ganesan, Career Breaks and How They Shaped Me and My Career, introduced me to a valuable Venn diagram: the tri-junction of Talent, Passion and Marketability (originally published in ReviewAdda: Career vs Job) -

The diagram and its message are mostly self-explanatory, but it allows a few key insights into this debate:

- If you have a talent for an in-demand skill, but you’re not especially passionate about it, that’s a job. It’s fine to do a job that you’re not passionate about. Sometimes, it’s even a necessity.

- If you have a talent for something that you’re passionate about, but there isn’t a market for it, that’s a hobby. And that’s fine too! Hobbies are important - and if there comes a time when this talent is marketable, you’re perfectly placed to capitalise on it.

- When your talent is also your passion, and there’s demand for it in the market - congratulations! You’ve found a career.

In this way, Kika’s talk was revolutionary for me, as it made me appreciate that sometimes, a hobby is healthiest if it remains as just a hobby. For instance, I love podcasting and will always continue to do it. However, unless I stumble upon a project with a significant (international) listenership, it’s never going to be a career for me. That’s not to say that I shouldn’t do it, but I should definitely be wary of how much of my energy I commit to it.

And, frankly, I’m currently trying to convert my coaching practice from “hobby” to “career”. I can recognise where I sit on the Venn diagram, based on the extent to which I’m finding my skills to be marketable. Until I have a substantial base of paying clients, I can’t call coaching a “career”.

(There are other business-related decisions to understanding where you sit within this Venn diagram: for instance, in the UK, HMRC has certain tax boundaries around self-assessment. At the time of writing, if you’re earning more than £1,000 per year from your “hobby”, then I’ve got news for you: you’re running a business, and the government wants to know about it, so that it can claim a slice of that pie.)

My encounters with converting passion

Weirdly, the closest that I ever got to finding true zen in “working with my passion” was my first big retail job, spending several years working as a sales assistant at HMV during my A-Levels and university studies. As a huge music and film fan, I was literally being paid to talk to the public every day about what I loved, including offering recommendations to customers, selecting albums for the in-store radio, and experimenting with how to position items to maximise revenue. It was so enjoyable that I gave serious (perhaps not serious enough) consideration to applying to be part of the company’s graduate training scheme, to pursue a route into retail management; it was only my desire to somehow make something meaningful out of an expensive journalism degree which put pay to that idea.

I chased this later in my career when I pursued a role with Last.fm, which definitely fell firmly into the “right job, wrong time” category. The company had recently been acquired by media conglomerate CBS, and were undergoing some major cost-cutting measures which hadn’t been revealed to users at that time; this led to a number of miserable months where my work involved removing features from the site and verifying that users (including myself, an avid user of the site) could no longer access these features. Still, although I was aware of these problems in my early weeks (and throughout my probationary period), I stuck it out for six months. This was my dream, I told myself, so why should I give it up so easily? (This was also an important lesson in not burning bridges - I maintained good relationships with my previous employer throughout this time, who openly welcomed me back when I decided that Last.fm wasn’t going to be the role for me.)

This is one of the biggest challenges of working in an area that you’re passionate about: you’re willing to swallow a lot more crap, to the extent that this could be leveraged against you if you’re not careful. This is most evident in the gaming industry, where unpaid internships (especially for games testers) are the norm - so many people want to do it, that they’re literally willing to give their labour for free. Even for paid employees, excess hours, crunch periods and burnout are still sadly the norm.

The passion obsession

There’s an excellent section in Rebecca Seal’s book Solo, titled “The passion problem”, which I wish that I could include in full, but it would quadruple the word count. In brief:

Saying that you’re passionate about your work shows a warped understanding of the word. (The Oxford English Dictionary’s first definition of it is “strong and barely controllable emotion”.) […] From a surviving-your-career-intact point of view? It’s unhealthy. Like busy-ness and working long hours, we have glibly adopted the idea of passion right into the core of modern thinking about work […]

I know how lucky I am to have this job, but it’s not my passion. I am not obsessed. In fact, I don’t even know what my passion is. I don’t think I have one. And that is 100 per cent, completely and utterly normal. Doesn’t sound it though, does it? Because we’ve been led to believe that successful people are following their passions, and that therefore, the two things always go together.

This is reiterated in a 2021 piece from Harvard Business Review, Your Job Doesn’t Have To Be Your Passion, which encourages the freedom which comes from keeping your passions flexible: by not committing to them as a career, you’re free to flex them in your spare time without the pressure of converting them into paying your bills. This is also evidenced in a BBC Worldwide article where a bookworm turned bookstore owner found his life being overwhelmed by work - to the extent that he no longer had time to read books!

If you’re making serious decisions about your career, the best advice that I can give you is to protect your love for the things that you love. Sometimes, this might mean committing to doing less of it (or, at least, under less pressure). If you’d like to talk to us about your conundrum, please drop us a line.

Key takeaways 📝

- If a passion or talent isn’t marketable, it’s not a career.

- If a hobby gives you joy, think what other emotions (good or bad) it would give as a career.

- Don’t let your passion leave you open to exploitation.